“The more you learn about the dignity of the gorilla, the more you want to avoid people,” said Dian Fossey, touching on one lesser known law of nature. One many of us prescribe to. One known as Nature’s Catch 22: a law of love and hate. The rule works on the basis that the more time you spend in nature, the less attractive the civilised world begins to look.

It is only natural to have your heart pulled on by the wild as she begins to open up to you. The more moments you get to share with her, with a leopard protecting its legacy in an ancient baobab tree, for example, or a whale calf swimming alongside its mother, so closely you can imagine them holding fins… It is only natural to want to shun the world you come from in favour of the wilder, purer, more dignified world…

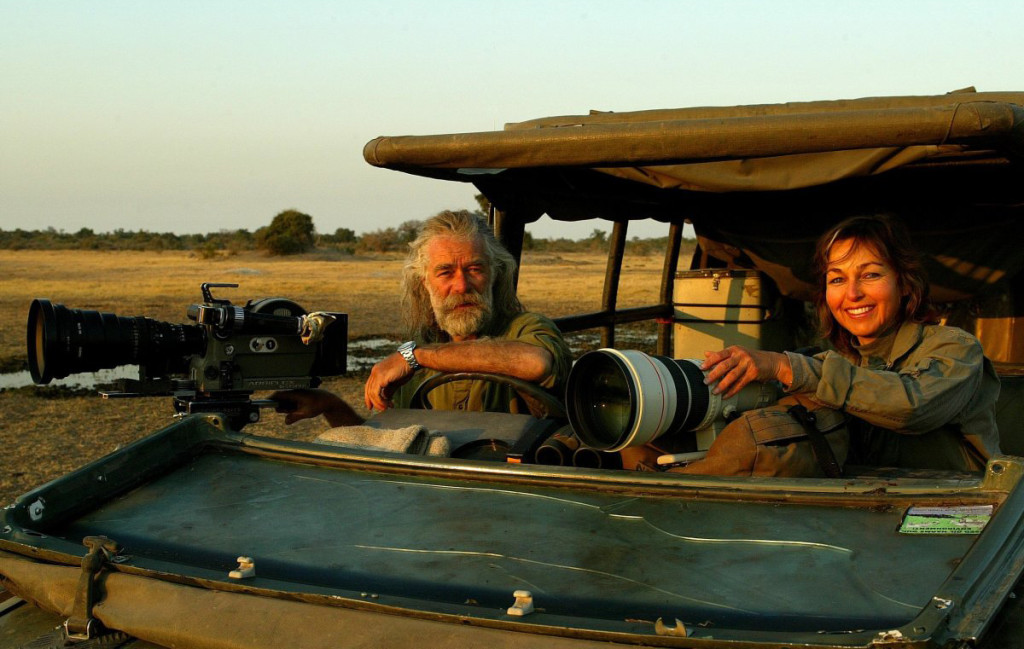

Image: Beverly Joubert

But then, someone comes along, a Dian Fossey or a Jane Goodall, and proves that dignity is not entirely lost on mankind. Someone like Dereck Joubert, who unravels your entire way of thinking in a second. Someone who takes a simple phrase that has defined so much of your life… I love not man the less, but nature more… and spins it on its head. Reminds you that nature is not separate from us, it is us. That the dignity of a gorilla is everywhere, in all things. And that all society needs is a little reminder…

Like Fossey and Goodall, the work of National Geographic filmmaker and Explorer-in-Residence and co-founder of The Great Plains Conservation, Dereck Joubert, together with his partner in the wild, Beverly Joubert, is exactly that reminder. In this week’s 10 Questions, Dereck presents a whole new Law of Nature (see Question 8), through his characteristic honesty and insight.

10 Questions with Dereck Joubert

1. Five important things to remember when living in the wilderness?

- Try not to panic, a cool head always gets you through.

- Panic when necessary, action is often needed, quickly and fast!

- There is very little to fear in the bush. People in cities do worse things to one another than any animal does.

- Breathe deeply, look around, soak it in, because tomorrow you might be on a plane to some city somewhere.

- Fight for integrity, yours, nature’s against extinction, against corruption, against greed. Everyone who wants to harm nature is the enemy, so fight them with wisdom.

Image: Beverly Joubert, taken in Botswana’s Savuti region

2. Five things being a filmmaker has taught you about yourself, life and love?

- No matter how bad it is today, if you consider one day writing your memoir at 99 years old, consider if this moment will even make it into that final book. Is it a 5/10 or higher in the scale of hardships in life. You will usually find that it is low, and not that bad. That gives you perspective. I can’t even recall how many times I’ve had malaria or nearly died. If your answer is that this moment is a 9.5 out of 10, then you know you’re in real trouble!

- Be in love, with the person you love… properly, as if there is no tomorrow. There may not be.

- Grab each day as if you were 20, or 99 there is no time to lose, no adrenaline too high to waste.

- Work harder. I add this because in those ridiculous sayings someone always says ‘no one ever wished they had worked harder in life.’ BS. Work hard, because having drive and passion is the fuel that keeps the engine running at a fine pitch. Lazy people have lazy minds.

- See life as if it is perfectly framed. Look for the good light, best composition, framing, because it will make you view life in a different, more perfect way. It makes life better if you can see perfection in an image you make, even if the image is of a slaughtered elephant, or people caught in rubble after an earthquake. If you don’t (as a filmmaker) live to make the moment inside the frame perfect, the content will get to you and mess you up.

Discover more about love in the wild in CBS News’ Married life in a tent. How do they do it?

Leopard of the Okavango Delta at sunset. By Beverly Joubert

3. How did you get involved in filmmaking and conservation – what drove you and continues to drive you?

Saving the world. From when I was young I knew that I needed to play an important role in life, not a spectator’s one. Filmmaking has a huge influence on the world, so we use it to influence people against destroying nature and to live a better life. Films can turn the world against hunting and toward kindness to animals. Without looking into the eyes of a gorilla or an elephant through the medium of film, 99% of the world would not know what we are talking about and just would not care. Without conservation, nature fails. Without nature, our souls wither, ecosystems fail, culture disappears, and it takes with it our integrity, our self worth, our common drive to strive for better. The eternal battle within each of us is mirrored in the way we interact with nature. If we lose this battle we don’t just lose animals, or litter a few highways. We lose our souls. I had a brother who was an artist, and from a young age I watched him create magical images from a brush and oil pigment. He made the world come alive through his interpretation. I hope I do the same, but with different tools. This is what excites me and has always inspired me.

Discover more about the Jouberts’ conservation work through the Great Plains Conservation, which along with several initiatives, includes three conservation-minded lodges – Zarafa Camp, Mara Plains and Ol Donyo. Image by Beverly Joubert

4. Favourite part about living in the bush and your wilderness home in Botswana?

Waking before dawn and feeling the crisp night air give way to the warmth of dawn as the darkness loses that battle to crimson light. I like the mist that creeps over the Okavango Delta and gives lions and buffalo the opportunity to play hide and seek in the nearly liquid blanket of white, their games of life and death being the very essence of this continent. The Okavango is a harsh but beautiful place.

5. Waving a camera in the face of Africa’s wild things must have led to a few daunting close calls.

We generally don’t wave cameras in front of animals. That is for TV personalities who want fame and reaction and usually get scratched as a result. We believe that when an animal sees and reacts to us, we have failed. Our ambition is to be invisible, wallpaper; to see, document, and be led into a magical world of acceptance. You only get this with respect and trust.

Some filmmakers choose a different path, playing with lions, or getting up close, getting charged for the camera. If we get charged we feel as though we have failed again. It is not our way. But yes, we have had many interesting interludes, because of foolishness, over-eagerness, other people’s folly. We have been charged a lot, by lions that have been previously shot or hunted, hurt or pissed off. We have been attacked four times by elephants, for the same menu of reasons. I’ve been bitten three times by deadly snakes, 20 times by scorpions, had malaria at least four times, crashed a plane three times and forgotten my sense of humour at least once, that I can recall.

What races through your mind in those moments? Are you more fright, flight, or fight?

I have the ability to be very calm. My mind focuses on survival. I am fortunate to usually have Beverly nearby and so psychologically I have someone I need to take care of. I have neither fright nor flight but often fight. A charging lion can mostly be dealt with by attacking and running forward. It is my default position to stay neutral until under threat – and only then attack. I abhor bullies and usually step out to prevent bullying of any kind. What races through my mind? Interestingly, I just wrote in a film script that standing in the path of a charging elephant is mesmerising – time slows. You focus on the dance of the flapping ears and the ivory look of the toe nails as they kick up dust in front of you. You merge with the animal in a way that allows a common language of communication, and yet, I don’t communicate or project thoughts, I just am. Neutral, neither scared nor aggressive. Mostly this has worked for me. A bully or two has bruised me – it doesn’t always work out!

Image: Beverly Joubert

6. Scariest moment encountered in the wilderness?

We are seldom scared. The wild is not out to get you. I think that nearly dying, losing consciousness and having a racing heart and lungs collapse from a double Boomslang bite may be the least pleasant experience I’ve had. But we both view each experience as just that, an experience – to absorb and hang on to, not one to get over and done with as quickly as possible. I love being in the midst of a challenge to survive. It is alive with energy. Having survived is kind of boring again. Right?

And most memorable?

Probably the time we spent with a leopard, one we found when she was 8 days old. Over the 4 years that followed she adopted us and absorbed us into her life. We were able to follow her each day. This was like a portal into a magical kingdom for us. It was a relationship like no other, where we never touched her, let her live her life and just followed. Yet she accepted us, sometimes touched us but trusted us to be there. Legadema was her name and a film and book came out about her and our lives together.

Legadema, as named by the Jouberts, meaning “Light from the Sky”, was featured in their book, Eye of the Leopard, and documentary of the same title, which won them their fifth Emmy Award for Best Achievement in Science, Nature, and Technology. Discover more about her in this TED Talk below.

7. How has your relationship with the African wild and her creatures changed over the years?

In the beginning, we were in awe of its scale and wildness, and wanted to absorb it all, take it all in, good or bad. As we did time, we came to understand that this icon (the wilderness), this over-powering, omnipotent Africa that so may fear, so many are in awe of, is fragile and on the verge of collapse. So we evolved our relationship into a nurturing, and protecting one. We spend our lives trying to understand it still, but now we convert it into action, advocacy, campaigns and battle strategy to save it. Is the fear factor still there? Never was. You don’t go in to the unknown in fear and turn it into a career. If you do, it is a short career and you leave as many do.

Image: Mara Plains

8. There is a beautiful quote by Lord Byron that goes, “There is a pleasure in the pathless woods, There is a rapture on the lonely shore, There is society, where none intrudes, By the deep sea, and music in its roar: I love not man the less, but Nature more.” How do you find alternating between the stillness and isolation of the pathless woods and hubbub of cities, airports and conference halls?

Philosophers and poets have always retreated to nature to find themselves, to find inspiration and meaning – a much more difficult task in the clutter of humanity. We were just in New York City at the Ivory Crush in Times Square -there are few more cluttered places than that. But Beverly and I were together and where we are together is the Centre of the Universe for us. We carry Lord Byron’s love of nature within us wherever we go because nature is not a place, it is an intellectual concept. It is a doctrine that also needs defending, and that does take us into the epicenter of the problem, like surgeons when they have to operate on a cancer. They don’t cut into the places where the body is perfect. We know that Man is the problem, the largest threat, and Man gathers in the hubbub of cities. So from time to time, that is where we have to go. To perform our surgery.

Image: Beverly Joubert

9. What is your favourite time of day in the bush and how do you to tend to start such days?

Early up, in the dark, usually between 4 am and 5 am, as we head out to catch the change in light. Nature is best when it changes. We all are. When it stays the same it stagnates. Savanna eco-systems thrive on change, as do we. Changes from summer to winter, thick forest to open grassland, night to day, alive to dead. Each of these is when energy shifts and we like to be there for each. That includes being there when lions attack and kill a buffalo. Not because it is exciting, it isn’t, but because it is pivotal, a sudden change that is symptomatic or symbolic of a change so vital. When the sun rises, we’ve usually been sitting with lions or leopards or elephants for an hour. We take mugs of tea on our drive. A dawn in camp is a wasted one for me.

10. The best adventure so far has been… the past 32 years living with, loving, exploring with Beverly. And the next adventure will be… the one we cannot describe yet, because without it being the unknown, it doesn’t really count.

Watch our innkeeper interviews with Dereck and Beverly, shot, of course, by Dereck and Beverly, at Zarafa Camp in Botswana, as seen below, as well as Mara Plains and Ol Donyo in Kenya, all unique lodges we are so proud to have in the Relais & Châteaux family.

Tell Us

What is your greatest take-away piece from our 10 Questions with Dereck Joubert?