Using sustainability and storytelling to create a better world

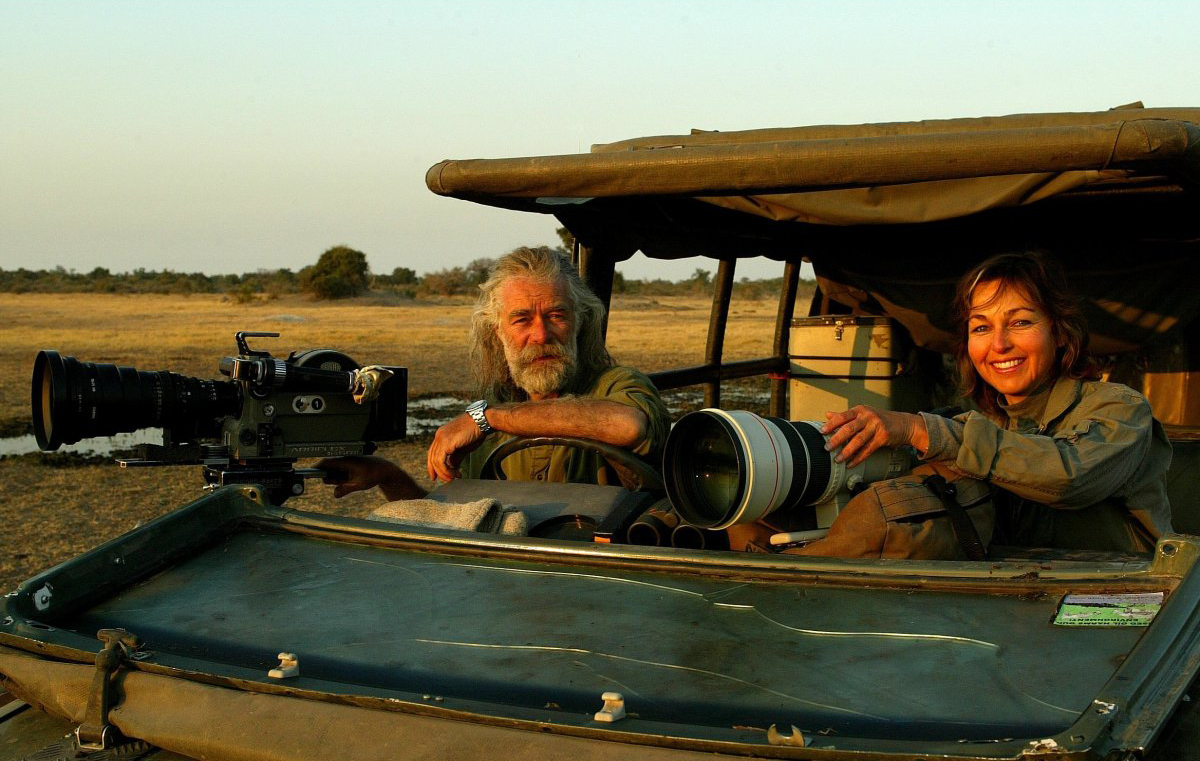

In several significant ways, National Geographic photographer and filmmaker, Beverly and Dereck Joubert, co-founders and owners of the Great Plains Conservation (with its Relais & Châteaux camps and lodges in Africa) are contributing to the essential health of our planet.

We connected with them to find out more about their work, with the Great Plains Foundation, and their philosophies driving the kind of change we need more of in the world.

One of the greatest takeaways from the interview below, for us, is the Botswanan concept of “Botho” ~ the art of care and respect for others, for the world. Something clearly at the heart of everything Dereck and Beverly do.

#findtheothers

Many say that before you can change or heal the world, you must change or heal yourself.

I think this is absolutely correct.

What do you think the role of the individual is in conservation?

Being fearless is important and standing up against atrocities needs a certain element of the explorer, a fearlessness. Many others will shrink away from difficult topics, or impossible projects like moving a hundred rhinos to safety for example, but by being a little bold we can achieve what is needed. Unlike, say, the hunting lobby that wants to kill for sport and entertainment, real conservation is not a hobby, so we should all be taking it very seriously.

How do you make sure to look after yourself and to continue to grow personally, while going about the great and demanding work you do?

The day starts with meditation and that stills the mind, then vigorous exercise before consuming anything, and that kick-starts the metabolism and of course tones the physical. During the day no matter what, we find time for gratitude because humility is key to our relationship with nature and other people. It de-stresses us, and it makes sure we have that mind, body and spiritual balance. But again, it is impossible to endure long sustained health with a toxic mind, in an unhealthy environment, so we do what we can to develop functioning environments that give peace rather than anger and bitterness.

We expel negative thoughts based on the notion that there will always be negativity around what we do, and we can tackle those that we can do something about, but those we cannot influence, we step away from. Love is the bedrock of what keeps us both ticking, and while it is solid the rest of our lives are impenetrable.

What has been your philosophy around sustainable tourism and how do you believe your camps and lodges in Botswana and Kenya reflect this and help to create a healthier, happier earth?

I don’t love the word sustainable actually, because it has embedded in it a hidden barb of compromise in certain contexts. It suggests that we would prefer to have no tourism but sustainable tourism is okay. It implies a balance between the environment and development. I think that some places need to have no development, and that often makes them unsustainable if our value system is simply dollars. Some places cannot pay for themselves no matter how much we try, but that doesn’t mean we should give them up to concrete.

Actually ALL our activities need to be environmentally sustainable as a core value, and anything that is not should be stopped. Tourism is a vital tool to creating passive interactivity with nature, where travellers can experience nature’s assets (peace, tranquility, oxygen rich air, wildlife wonders, waterfalls, deserts, amazing mountains that inspire one to be fitter, more caring and to love the planet) and to do it without taking from it.

You can do that for free, or you can be charged thousands a day for it, the value transcends the price. We add a layer where we invite guests to our camps to expose them to beauty in nature in the hope that they will take that appreciation away to their lives and do something in their world to match this or be inspired by it in their own way. You can live a healthy life in a healthy environment in thousands of ways across the planet.

Our experiences do a few things. They expose guests to new insights, new versions of themselves, new cultures. They inspire creativity, thought, advocacy for the planet. They make us better people.

A part of our philosophy is to leave no footprint, touch lightly, but that is largely our job as hosts, what we pass on is the philosophy that doing this doesn’t mean one has to compromise on quality, and that is probably the single biggest thing people take away and can adopt in their lives. No one wants to have to live like a hermit in New York, but they can start considering greening their building.

How about the use of solar energy, biogas, recycling and the like?

These are the tools of our business, and we display them openly as an example of what can be done. Many people are blown away knowing we can do all this, 13 hours drive away from a store. But it extends that story of ours about doing better and doing what you can. So a biogas cooker from discarded vegetable matter can also produce one of the best gourmet meals in the world. Again, an example of how we don’t have to see “green and sustainable” as a compromise on quality.

You are involved in significant conservation projects working to actively effect great change on the ground when it comes to saving Africa’s endangered animals and protecting her wild spaces.

We are and they will be worth waiting for, because we are ramping up our work to a more global scale.

What are some of the successes from these projects that mean the most to you and why?

Conservation is a balance between wildlife, space and people, a partnership between us all. One example is our Rhinos without Borders program, where we raised over $6M towards moving 100 rhinos from high poaching areas in South Africa to much safer zones in the wild in Botswana. We’ve already had 23 babies. Another success is the Massai Olympics project that we support, designed to create an alternative for warriors to killing lions. Lion killings went from 40 a year to just 1 in 4 years. We do make a difference, all of us.

What chance do we stand, in your mind, in the mission to save these wildlife from extinction and to protect and preserve wild spaces?

We are at a tipping point right now to be frank. Within a decade we will know. For example, two years ago we reached a point where rhinos were being poached faster than they can breed. But more and more the world refuses to accept actions that damage the global commons and then we weigh in. Long term, with 8 billion becoming 10 billion people and consumers of resources and producers of waste, on the planet is a challenge we will all soon be focusing more and more on. But we have the most amazing ability to rally behind causes: ozone, plastics, cruelty.

The answer will be in how we ‘care.’ There is a saying in Botswana; “Botho” – which is a catch-all for ‘respect and caring.’ If we hang everything on being caring it negates us doing anything that is damaging.

What gives you hope in this great fight?

Women, largely. Women fight for their home, their circle of caring and if we view the planet as our collective home, we need women to lead the charge to protect it. I don’t think that negates the work that men need to do, or that it is one or the other, but I am inspired by women and the style they use in getting things done. While we suppress the voices of the young and women, we are not using over 75% of advocates for the wild. I want 100% attendance!

How do you believe photography and film (and other forms of storytelling) can create a better world?

All storytelling creates a better world. We are the storytelling “ape”, and we define heroism and great journey’s by the stories we tell. We are all the main characters in our own stories, so not loving our story lets us down, not living up to the ideal version of ourselves in our story, disrespects our potential as humans. Using the tools of film and photography, music and dreams we tell stories about wildlife but in fact they are just parables about the human condition.

There is a Latin phrase, Homo nosce te Ipsum, something I live by, (it means, Man know thyself) and I believe that if we know ourselves, we can know others, and then we can know and care for everything. It sits alongside our ability to forgive ourselves. Our films drive understanding and parallels that I hope audiences see and learn more about themselves from, as members of a larger community.

How do you attempt to achieve this through your photography and films?

We tell stories of beauty and intrigue, tales that inspire audiences to want to fall in love with nature, but then we always move beyond the visceral to the intellectual with stating or asking questions about conservation or the role we play in the preserving this beauty, or destroying it. A film is a journey into a story that dances between the heart and the mind, an internal dialogue, that if you get it wrong, the piece can be too preachy or it goes the other way and ends up without any meaning at all. It’s an art we started developing 3 million years ago when we discovered fire, and that freed up time for us to extend our days, sit in the warmth and light and tell stories.

As far as conservation, ethics and legalities are concerned, what are the big no-no’s when it comes to wildlife / portrait photography and filming in Botswana and Kenya, and in general?

Non-disturbance is a strict discipline for us whether it is, in the camps and in the field when we are filming. So we are hyper sensitive to what animals are doing and often say that we have failed in what we do if the animal looks up at us, and failed twice if it stops its behaviour and reacts to us. So when we watch TV and see an elephant charge we know that someone disturbed an elephant and it is not ethical. But I think the film-making ethics are the same as life ethics, be truthful, be kind.

What do you essentially try to say through your art?

It varies but the essence that is consistent is that we live in a beautiful place and we are all going to have to clean and maintain this ‘house,’ or it will fall into disrepair.

In the Relais & Châteaux Great Plains Conservation camps and lodges, the Great Plains Foundation, and your photography and films, how important is the role of community and collaboration for you?

We are the storytelling “ape”, but we are also communal beings, where sitting around a meal and discussing things are some of our happiest moments. Preparing meals together and sharing with that community is essential. That is why we are putting interactive kitchens into our Relais & Châteaux camps and promoting executive chefs and making use of that communal spirit.

What we love most about Relais & Châteaux is that sense of community. Each time we return from a Relais & Châteaux Congress, where the finest hoteliers and hosts in the world sit and talk about the art of hospitality, I know our camps gain from my advanced exposure, gain from what I’ve learned here, and get a little better.

There is something heartwarming about getting a letter from someone who has travelled around the world but finds a camp like Duba Plains Camp or Zarafa Camp ‘simply the best in the world’ and we get there on the shoulders of our Relais & Châteaux friends.

How do you approach and harness the power of community?

We work closely with local communities, and we are just designing the Great Plains Academy in Botswana, where we will take students of hospitality and conservation and get them ready for university-level further learning. It will teach business skills as well, and through this I hope that the communication between us and the communities we work with will increase, as they become partners in our future.

We of course support them via leases and donations, teaching, conservation camps and solar projects, but it is the empowerment of the community that we are most interested in so we can see real investment from their side in tourism.

We also partner with our guests to get them involved, help fund our projects and to expose local communities to them in a two way conversation. We teach our staff that they should be aware that they have access to our guests as an informal university of life. Our rhino project was a partnership with an opposition company, so we partner with everyone!

In the Relais & Châteaux Great Plains Conservation camps and lodges, and in your personal lives, how do you align the art of gastronomy with sustainable living, with health and wellness, and with conservation?

Well, our food is an extension of our overall philosophy of healthy mind in healthy body in healthy environment. So we try to connect our story of this balance from the vehicle with lions and elephant viewing and the snacks you might get served at sunset, to our wellness spas, to food in rooms, to all meals and drinks. It is based on plastic-free delivery in all our camps, and that includes water bottles, (no plastics) to having no single use plastic wraps in kitchens etc, but also on the freshness, and whole food. We don’t serve anything from a packet (plastic or otherwise) and I drum into everyone that if we can buy it and pour it into a glass or bowl, as is, it has no place in Great Plains. Here, a gin and tonic is a mix of botanical herb gin but mixed with our own blend of citrus. A fireside snack is made by the chef and has to have gone through a loving cooking process.

We use mostly sugar-free alternatives, no garlic or onions (because they are toxic) and alternatives to dairy and wheat at every meal. But we do that with the ambition you would not know if it was gluten-free or not, of that the chocolate was made from avocado and coconut. We don’t serve ocean fish at all, except salmon. We don’t hunt and kill; there is no game at our camps. If you can photograph it in the day you cannot eat it at night at Great Plains!

We are embarking on setting up community farms in most areas and in Kenya about 80% of our fresh food is grown on site. We like to buy locally for freshness, but within in the context of great produce and freshness and of course extremely remote areas. Sometimes growing locally in camp, is environmentally damaging and attracts elephants and monkeys, and we hate chasing animals, so either we plant for them (which is unethical) or we don’t plant at all.

If our lives stand for anything it is about being caring and respectful.

Ironically, that in itself places us in conflict if we have to speak up for elephants or the environment and even fight for them. But it’s all about having a conviction. And Botho.

Follow Dereck and Beverly on Instagram for more updates and tales from the field:

@dereckjoubert @beverlyjoubert